The Cycling Training Software Market is Highly Fragmented

And this fragmentation is hurting everyone.

Editorial Note: This article was originally published on 2017-02-09 on Medium and is still available there at the time of writing. I re-publish it here for two reasons: First, I want to have it under my own control. And two, as much as it pains me to say, it is still relevant. This is part one of a series of three. Here are parts two - Helping Athletes see a Bigger Picture, and three - The Planning Conundrum. I have also added a commentary to add some perspective. I’d like to thank Eric DeGolier from Body Rocket for unearthing these articles and helping me re-discover some personal ancient history.

The original article:

*Around New Year 2017 we created an online survey to get a better understanding of how users incorporate software into their everyday training. Specifically, which software (or combination of software tools) they use, and why. The ultimate goal is to help the development of a new user experience for the Open Source training software GoldenCheetah, but we hope that the results are found to be helpful beyond this scope. You can download the report at the bottom of the page if you’re looking for results and a bit more context. In a series of articles, I want to reflect on the findings, and explore new insights.

In the first article of this series, I want to talk about what is the most obvious result of the survey: The fragmentation of the cycling training software market.

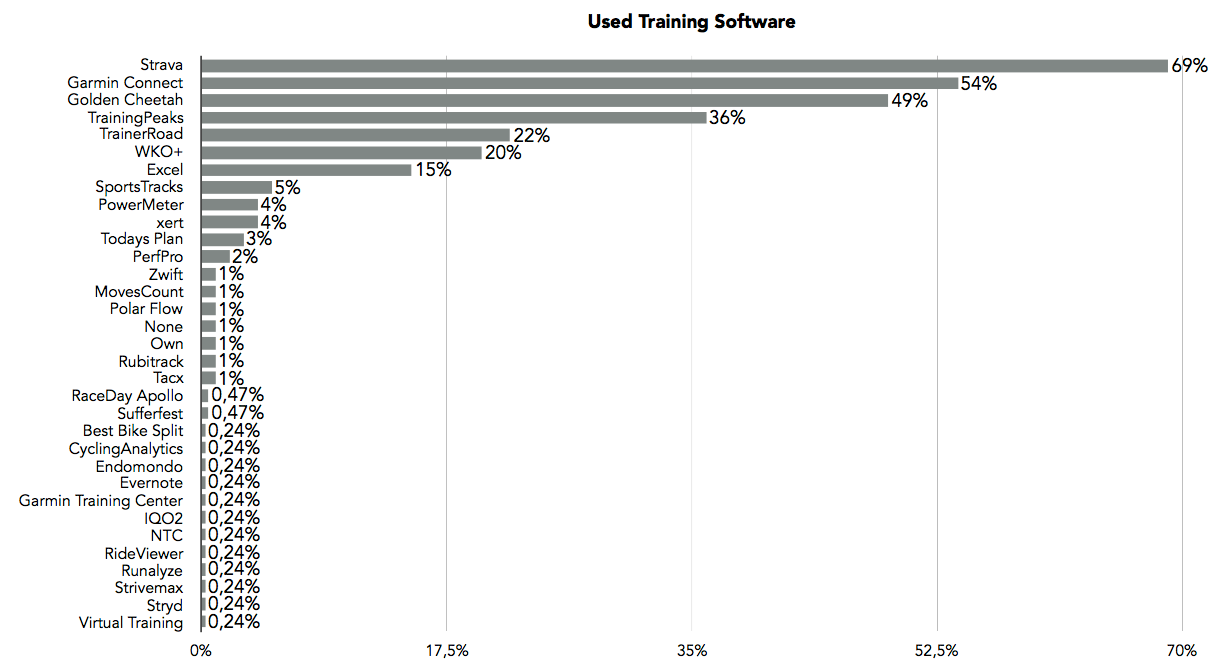

When asked what software tools they regularly use for managing their cycling training, 421 (out of 424) respondents mentioned a total of 32 different tools. And if you look at that list, there appears to be a clear winner in the form of Strava, which is used by 69% of respondents. Only one other tool — Garmin Connect — is also used by a majority of people (54%).

This sort of distribution is not uncommon: A few popular software tools that are relevant for the general market population, and a lot of special-use tools that have a very small market share (the top three mentions in this survey make up more than half of all answers).

But this is only part of the story. If you don’t add up all mentions of a software tool but count all combinations of tools, you get a different picture. If you look at the data that way, Strava is still the most popular software choice. But only 7% of Strava customers (paying and non-paying) use it exclusively. All the others use it together with at least one other tool. So, although Strava is very popular and widely used, it doesn’t satisfy all of its users needs, who look elsewhere for other options.

When you dig into the data, this is a pattern that holds true for every software option. What we found is not only a fragmentation in vendors, but more importantly a fragmentation in usage.

A Fragmentation in Usage

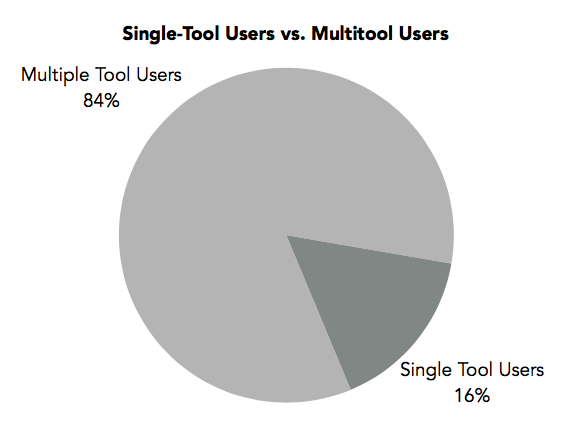

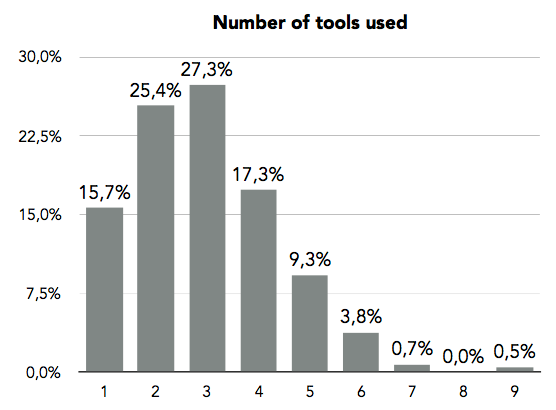

You can see this fragmentation in usage by looking at the number of people who use more than one software tool. And this number is very high: 84% of respondents use more than one tool for their day-to-day training management. Most of them (70%) use between 2 and 4 tools.

Having a crowded marketspace with lots of different software makers competing for the attention of their audience is not exactly rare. Think about ToDo-List-Apps, where there are lots of vendors, but users typically stick to the one solution they like best. It would be quite rare to see someone using Wunderlist together with Remember the Milk and Google Tasks and manually syncing data back and forth (or using an automation service to do it). Yet, this is precisely what is happening in the cycling training software market: Users find all available options lacking, and start adding pieces together to build something that works for them. This fragmentation in usage has important consequences.

Interestingly, there is no common combination of tools. You might think that for example people use the two most common tools — Garmin Connect and Strava — together in order to get a more feature-complete solution. For example, using Garmin Express to upload a workout file to Garmin Connect, which then syncs to Strava.

Only 8% of respondents use this specific combination of software. Think about that for a second. And all other combinations are equally rare: No combination of tools gets a marketshare that is greater than 4%.

And even if we check for combinations of Strava, Garmin plus one or more additional tools, things don’t get much clearer. In this scenario, Garmin/Strava/other has a share of 43% (which is still way lower than I would have expected).

Two paths to a better user experience

The most obvious interpretation of these facts is that the vast majority of users are completely underserved by the software in the market. They need at least two different tools to accomplish what they want to do, and most of them need three software tools.

It also means that all software tools are overspecialized into a set of features that may or may not serve a specific audience — and as it turns out, it doesn’t. Because if there is software that has a very narrow target audience, we’d still find more people who are using only one tool — the one that was made for them. So, it looks like most vendors created their feature set based on a certain technology or a certain idea, but not on needs people actually have. The result is a very questionable user experience. And that is hurting everyone involved.

From here, software makers have two possible paths to creating a better customer experience:

One, to create a feature set that aligns with the needs their users actually have, eradicating the need for other software. To that, they have to look at their “companion tools” and understand why people are using them all in combination to figure out what their offering is lacking.

Two, make integrating all those tools extremely easy. Automagical data syncing would be the minimum requirement.

Two is easy, and quick. One is harder, and takes longer, but ultimately leads to a better understanding of your customer base.